The following interview took place by phone on April 11, 2011. Stan Douglas spoke to me from his Vancouver studio. The interview pertains to the artist’s “Midcentury Studio” exhibition, which debuted at New York City’s David Zwirner Gallery March 23, running to April 23, 2011. My Globe and Mail piece digesting this interview can be found here.

Tell me about Shoes, 1947.

This is kind of half-way through the guy’s career. He’s doing various genres: pickup work, piecework. When there was an opportunity for a photograph, he’d go: a news story, occasional work for advertising, etc. This would be a fashion shoot—obviously, advertising some shoes. This photograph, like many of the photographs, is based on making a situation—having various models and pairs of shoes and a location we could work out of. LIFE photoshoots [of the time] … prepared everything. Setting up, practicing the lights. A lot of them were cropped, in the end. In this case, we’re seeing the whole thing. In the [final], one would imagine we’d only see the shoes, partly up the calf.

Here, the model’s pose is very uncomfortable. It’s not a natural way of standing. It’s very difficult for the model to actually hold this position, to keep balance. We’d typically just be looking at a profile of the shoes side-by-side. But we’re being shown a bit more than that. Her hands and forearms are responding to what’s going on with her feet down below. And of course she’s decapitated, much in the way that we see in other works [in “Midcentury Studio”]—body fragments, body parts, implying an external space that’s not being revealed. It gives an uncanny effect. Her hands tell the story of what’s going on here.

So did you intend to have the fists?

No, that just happened. We were trying various shoes, various stockings, various models, various floor surfaces. We had a tapestry that we rented but never actually used in the end. But I saw what was going on in terms of her difficulty and thought it would be appropriate to include that in the image.

These images aren’t to a large degree composed. I don’t have a composition or shot to which I’m trying to make reality conform. As I said before, I’m more or less making a situation and improvising within that situation to get an image that’s workable.

It’s ironic, as the show seems so much about composition and technique—the classical aesthetics of analog photography.

The camera was criticized for a long time for its automatic quality: that there’s a machine involved, and that images were being produced without the complete attention of the artist or picture-maker. But that collaboration with reality is the thing that makes photography so fascinating. In spite of that automatism, there are a lot of things that a camera can do that may or may not be within the photographer’s control. It’s very different from now, where we have programmed digital photographs which, to a certain degree, determine the kind of photograph being made. Every photographic apparatus has a limited number of photographs it can make. Granted, this is a very, very big number of images, but it’s limited by the technical makeup of the apparatus. What’s happening now with cell phone photographs, which we’re seeing on Flickr and Facebook and the like, is that images are being made with a program that is very restrictive, that defines what a good photograph should be in terms of focus and exposure. There are even cameras, now, that will not take a picture until someone is smiling. We create that convenience [in the face of] the creativity of earlier, more manual modes of image making.

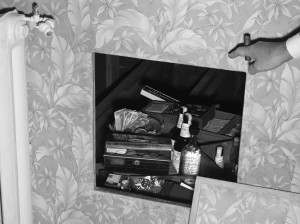

Tell me about Cache, 1947.

There’s something I was interested in doing with all of these photos: referencing one of my favourite works of art, the Scrovegni Chapel [frescoes] by Giotto—and the image of a hand appearing out of the sky. I kind of overdid it with this series: things pointing, things coming out of the corner of the frame and being part of the image. This image is kind of a combination of a Black Star image—things you’d need to run a gambling or party house—and an image I saw from when the police were investigating Lee Harvey Oswald, which looked into a window of Oswald’s house and had a hand coming in from a corner pointing, on the other side. These things all kind of combined in my mind to make this picture. And there’s the cards, the dice, the cash, the smokes, the booze… everything you need to have a good time.

And the hypocrisy of the cigar in the pointing hand. Where did you take the shot?

Quite a few of the shots including Shoes, 1947 were shot at an old mansion referred to as either the Cenacle or the Rosemary that’s in an area called Shaughnessy in Vancouver. A 1920s house with a lot of elegant fittings. It was really important to try to get period door handles and construction methods and have these things visible in the architecture. It’s kind of hard to find places in Vancouver that still look like that—like they might have looked in 1940-something. [The intention was to have a] 1920s building that[, from the date of the fictional photographs, looked] twenty years old—had been kept up so it still looked [as it originally did]. The rafters you’re seeing inside the cache are the structural rafters of the house. The radiator outside [is authentic]. We actually applied the wallpaper to the wall to get a different look to it.

And the nature of the photograph is something that would be part of this fictional photographer’s career, following police investigations and illuminating them through his work?

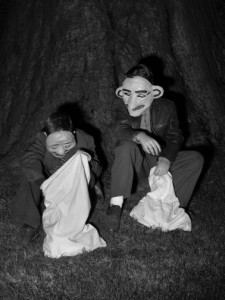

If you look early on [in the series] you see there’s one photo done when he’s in the army—Camouflage, 1945, which is early product work. There are random things after that, like the kids trick-or-treating [Trick or Treat, 1945]; the portrait of the athlete [Athlete, 1946]; the portrait of the horse [Horse, 1946]; the images of magicians or from sideshows or something. These might be cases in which he has talked his way into a job. Later on, he was more into doing fashion things, hairstyling things. That was another phase. Again, there’s piece work, in the few images that show crime scenes. Like, Weegee would go and try to find something that had taken place, get an image, and try to sell it on spec to a newspaper. Toward the end of his career he’s more involved with set-up images, where he’s collaborating with the subjects to make the thing happen. You see this in LIFE magazine: as they try to have more social relevance or significance in their photographs, they become less and less documentary, less about taking a picture of what was there. It’s a matter of the photographer organizing what was there to make a more interesting image.

So there are aesthetic interventions on top of the improvisations.

Yes. Like, the dice players [Dice, 1950]: if they were really playing dice, they’d probably be pissed off at this flash going off as they were doing it. The guy who’s got the worm-digger light on his head [Worm Digger, 1949], it’d have to be a very long exposure; it’s 4×5 film, so the guy would actually have had to stand still. In some cases he might be running in [to take the photo], like in [Suspect, 1950]. In Cricket Pitch, 1951, he’s actually in the middle of the cricket pitch to get that photograph. He’s been allowed to do that by the players.

I want to go back to Athlete, 1946. The thing that struck me most about this and a lot of the images was how much you paid attention to period physiognomy—how “1946” this guy looks. What was the casting process like?

Mostly looking at extras. In that situation you have lots and lots of choice. Actors often have a specific look, and always try to look good. The problem with actors is that they’re afraid to look unusual and odd. Extras are not necessarily as trained, but do have a particular look that some photographer or filmmaker is going to want to use. Getting people who reflected that 1940s diet, say—that was difficult, but it was something we were able to find by going through a thousand or so headshots.

What sport does he play?

Baseball. There are details indicating this in the shot.

Where was this shot?

The basement of the Rosemary. Again there’s the paneled walls, the hinges, the wire that’s made of asbestos. Totally period stuff.

And this is based on an existing photograph?

A couple of pictures. [During the period,] a number of photographs were done in the locker room, portraits of those athletes and managers and that kind of thing. I like how they were photographed in these dank, stinky dressing rooms, with no real regard for how this would frame the subject. The photographer just went in there and was like, “Here we are; here you are; I’ve got my camera; bang, let’s shoot it”—not thinking about how it was going to look with the moldy floor, the dirty walls, those kinds of things.

But did a genre develop based on that haphazardness?

Things would happen by mistake. What he [i.e. Douglas’ fictional photographer] was trying to do was photograph one person, but forgetting about what the background was like or what the rest of the frame was like. Occasionally, just by accident, you’d get quite astonishing compositions from that situation: not much regard for the whole composition, but it becomes part of the thing. I knew what the place was going to look like. We had to dress it; we had to get all that old sports equipment in the back room; we wet the floor down. These are things we knew would give the right look to the situation.

Moving on to Smoke, 1947. What place would your fictional photographer have in photographing magic and sleight of hand things?

I guess he would be doing the shot for the magicians: pickup in the glass case in front of the theatre where they’d do their thing. But often getting the wrong moment. In this case it’s something that’s just disappeared, but you’re not sure what that thing was. It’s kind of an odd strategy, to take that view of this guy’s work: giving an image of having just missed whatever was in the smoke’s place.

I had a couple of magicians come in for the shoot and sat down with them and just asked, “So, what can you do? What involves a lot of motion, transformation? How do we make this into something?” They’d show me their routines and we came up with a few things. One of them was this disappearing object on this funny, Orientalist-looking platform. And the rings [Rings, 1947]: after a number of takes, you get an impossible-looking combination of rings.

The how-to-steal-a-watch image [Watch, 1950] was more journalistic, and would have been used for illustrating some kind of article about something—warning you about shaking hands with the wrong person. We had someone in to see if they could pick somebody’s pocket, [but ended up doing] this watch thing.

What about Incident, 1949? Obviously it was your intention to include at least some photographs that were reminiscent of Weegee. The intimate space is interesting. And is that a real body under the newspaper?

Yes, and it’s actually a period newspaper. We got it from eBay. In this case I like the wonkiness of the building; we were seeing structural things intruding into the otherwise clean space of the stairwell. Certain things from the outside were intruding into the interior space. We did have to add that wire, which is hiding a more contemporary power line. Originally, I was just going to shoot the corpse by itself but kind of realized there wasn’t much going on. We had this guy dressed up like a police officer from a different shot, and it didn’t work out; he was one person too many for the shot. So we just thought we’d bring him in and see what he could do there. It’s funny, the dialogue between him, making eye contact with the head underneath the newspaper, the odd negative space—it’s almost like a coffin with that notch, which is almost [fitted to] his head.

We aren’t used to photographs of this specific kind any more, though they’ve come to define the era you’re representing, along with film noir.

I guess photographers can’t get that close, with crime scenes being taped off. In this case things happened slower. The person who saw the corpse wanted it covered up, hence the newspapers. This was done in the period. The other photograph [Burlap, 1948] —it’s unclear as to what that is. If you think about the scale of the planks on the floor, are they big enough for a body to be there, or not? It’s weird. Could be a dog, or just some tools under burlap. It’s just a strange, undulating form. And where is it placed? A covered bridge, an alley? We don’t know. These ambiguities are at play. This, Cache, 1947, Burlap, 1948: these would be more piecework. Some news event that’s gone on: this photographer tries to get into it and sell it to the paper.

You’ve built such a narrative around each image and the photographer’s career. It’s almost like method acting.

Well, you start doing research to a point where you know how things should look, how people should behave, and then when it comes time to make the picture, you are able to recognize when it looks correct or false. Or, true to the period. The whole thing is the arc of a career. It’s a narrative in which you look at the breaks between images, much like we connect the breaks between shots in a film, that negative space of the edits in which we have a fantasy that either makes a character talk to another character, look at some other thing, some other person—jumps in space, jumps in time. The gaps between these images tell the imagined story of the guy’s career, which he’s negotiating in the post-war period.

Is there a reason why, at David Zwirner Gallery, the photographs weren’t all arranged chronologically?

It didn’t look good. The monograph, the list of works, will tell you the order of things. I made these images one by one so I wasn’t so much composing it to look like a single thing on the wall. They’re grouped thematically; things just go together. The back of the head, the hair [Hair, 1948], goes very well with Shoes, 1947—one kind of decapitation with another. And so on.

Two last images, Hockey Fight, 1951 and Suspect, 1950. With the first: are there a lot of instances in archives of Canadian photography of brawls at hockey games?

One photographer that I based a lot of the work on, Raymond Munro, has one photo of a hockey fight. In fact, it’s in the same building I believe, [Vancouver’s] Kerrisdale Arena, where we shot this. [In Munro’s image,] there’s a fight, and this concentric circle of looks and pointing fingers, but you can’t actually see what’s going on. The source, the nexus, of the fight, is hidden from view, but we see everyone trying to look at or get away from what’s going on. I played with that a while, to see if it would work for me to have a dense collection of people overlapping. In the end, I thought it was more interesting to have some sense of the looks between the characters—the man falling down with that extreme look on his face; the concerned look of the woman at the right, who is looking at the man being pulled up and down at the same time. That’s the punctum of this photograph.

The perspective is also interesting: the photographer in a press stand?

He’s in a press booth, yes. I was photographing from a catwalk, of the press booth of the hockey area where the photographer would be.

Is there a basis for Suspect, 1950?

In a way. There’s an image from the Black Star collection of Latin American delegates at a conference in Savannah. [I liked] the look of suspicion that these guys have, or actually the obliviousness of these guys to the photographer, and the suspicious look they’re giving back to him. What you might imagine [in Suspect, 1950] is a lawyer, a suspect, and his henchman, going from left to right, but the thing I really liked were the glasses of the suspect, which obscure his eyes, but you can just barely see through them. There’s a delicate, threatened look in his eyes as he stares back at the lens.

There is a sense of threat in so many of the images, as if the profession itself was a kind of warfare. What kind of risk did photographers like your fictional one in the show take?

Well, I guess there was always the risk of getting punched in the face. But what I find genuinely interesting here is that this is not WWII, a well-documented period, or the 1950s—at least as we know them today. The kinds of images you see in this photography would never have made it into the mainstream press in the 1950s. This is a period that is not often talked about, postwar North America. People had to do desperate things in order to make a living.